Legacy of Innovation and Risk

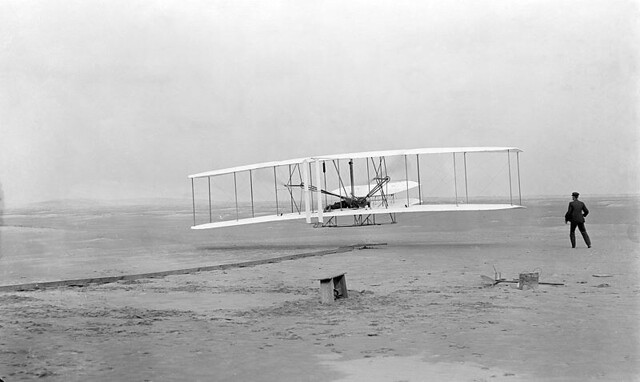

One hundred and twenty-two years ago the first powered aircraft carried a man one hundred and twenty feet in twelve seconds. Since that day, there has been a wildfire of innovation within the aviation industry.

After the new technology that came from World War Two, the “Golden Age” of aviation began. This boom in commercial air travel revolutionized how people all across the world lived every day. However, a quick start and lack of experience turned deadly. This discussion is going to pay particular attention to the development and history of aviation safety programs in the United States. To do this, we must go back to the beginning. The first government controlled aviation service was the Air Mail Service which started serving across the country in 1918.

The service used government-owned planes, flown by government-employed pilots, and in a marked contrast to the norms of the day, placed a strong emphasis on safety. Elements of the safety program included strict criteria for selecting pilots and requiring regular medical exams for them, careful aircraft inspections, the use of a 180-item checklist at the end of virtually every trip, and regular engine and aircraft overhauls every 100 and 750 hours, respectively (Hansen et al., 2008).

The Push for Safety

While these practices were quite arduous and dedicated many man hours, they set the standard for safety. In fact, this is what caused a push for the federal government to provide safety oversight in all aspects of aviation. Shortly after, congress passed the Air Commerce Act (ACA) handing over control to the government. Those who authored this act saw it as a push not to regulate, but to promote. This liberal approach subsequently led to a higher accident rate compared to those organizations and pilots who followed all regulations. Slowly, regulations began to tighten as leaders gained more knowledge on what steps to take. It is famously said that, “all aviation regulations are written in blood.” This is proven beyond a doubt in the early history of aviation. Flashing forward to 1938, the Civil Aeronautics Act (CAA) was passed consisting of an administrator with a board and an air safety board whose primary responsibility was to investigate accidents. Continuing forward, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) was created in 1958. This organization still regulated air safety in the United States to this day. Because of this organization, despite seemingly monotonous bureaucracy, air travel is the safest it has ever been. In the time since 1958 several safety enhancing programs have been created. These include the Maintenance Event Decision Aid (MEDA), Aviation Safety Reporting System(ASRS), and the Aviation Safety Action Program (ASAP).

Learning from Human Error

The Maintenance Event Decision Aid is an idea that one or more contributing factors causes an error resulting in an accident. The word “cause” is used loosely in this sense. It is more so increasing the probability of an event occurring. This program pushes deeper into the cause of events resulting from a lapse, or several lapses, in judgement. Ultimately, most of these are under management control. Therefore, to reduce the probability that an event will occur in the future, changes must be made. James Reason put it this way,

But human error is a consequence not a cause. Errors, as we have seen in earlier chapters, are shaped and provoked by upstream workplace and organizational factors. Identifying an error is merely the beginning of the search for causes, not the end (1997, 125).

Not Just a Problem in Aviation

Ultimately error is the result of the type of culture created within an organization. This does not apply only to aviation. For example, electricians. This industry is arguably just as high risk as aviation. People’s lives are at stake and mistakes can harm both worker and customer alike. In the same light, a culture of safety has not been implemented across every organization in every aspect as it has with aviation. There was an electrician, let’s call him Bob. Now Bob had only been with the company for a few weeks. As he was working at this jobsite, there was a time crunch to finish. The customer had plans to use the facility in only a few weeks. Bob was wiring ceiling lights into a 277v circuit (this is more voltage than your typical wall outlet in a house) for at least 8 hours every day. During this, he expressed concern about working on the wiring without turning off the power. His supervisor quickly dismissed this concern. Having little experience in this line of work, Bob took this as unequivocal truth and ignored his gut. Really, the supervisor had been unable to find the circuit breaker going to those particular wires. He was also pressured not to kill the power because part of the building was still serving as an office. Only a few days later, Bob was standing on a ladder and got shocked in the hand by a live wire. This event led to a trip to the emergency room. Now, was this Bob’s fault? I would argue it wasn’t. There were several contributing factors that led to this event. Moreover, the event was not reported as a way to increase organizational safety. In this regard, the aviation industry has done extremely well.

The Power of Safety Reporting: At the National Level

The Aviation Safety Reporting System (ASRS) was put in place as a way for anyone in the aviation industry to report safety incidents without the fear of retaliation. This system actually protects from charges if the action was not a result of gross negligence. Beyond a protection for the person involved, the reports submitted to NASA, the organization that sponsors the ASRS program, are an invaluable source of data for the aviation industry.

Human intervention in naturally occurring change can nudge change in a positive fashion. Healthy, productive organizations do not resist change, but forge it in a way to enhance the organization. This is true for product type, market share, mission, corporate processes, structure, and every aspect of the operation. It is also true for safety processes and risk reduction methods (Alston, 2016, 96).

Human intervention in naturally occurring change can nudge change in a positive fashion. Healthy, productive organizations do not resist change, but forge it in a way to enhance the organization. This is true for product type, market share, mission, corporate processes, structure, and every aspect of the operation. It is also true for safety processes and risk reduction methods (Alston, 2016, 96).

The Power of Safety Reporting: At the Organization Level

The Aviation Safety Action Program(ASAP) acts in a similar manner to the ASRS. Its goal is to,”enhance aviation safety through the prevention of accidents and incidents. Its focus is to encourage voluntary reporting of safety issues and events that come to the attention of employees of certain certificate holders” (Federal Aviation Administration, 2025). This program is not used as a means for the government to take punitive action against organizations. Rather, according to FAA Advisory Circular 120-66C,

The primary objective of voluntary safety programs is to identify hazards and unsafe conditions in the National Airspace System (NAS) so that corrective action can be taken to eliminate or reduce the hazard or unsafe condition. Aviation safety is well served by incentives that encourage entities to establish programs to identify and correct their own instances of noncompliance while investing in the prevention of recurrences. The FAA’s policy of forgoing enforcement actions when one of these entities detects violations, discloses the violations to the FAA, and takes prompt corrective action to ensure that the same or similar violations do not recur is designed to encourage compliance with FAA regulations, foster safe operating practices, and promote the development and maturation of effective Internal Evaluation Programs (IEP) and Safety Management Systems (SMS).

Regulation and Investigation

As we have been discussing, at the heart of aviation safety in the United States is the FAA and the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB). These two agencies collaborate to recommend and implement rules that increase safety in the National Airspace System (NAS). The reason this is such an effective relationship is because they are separate entities that cannot influence one another. The NTSB provides an avenue for aviation professionals to appeal FAA enforcement actions. The NTSB also serves under the Department of Transportation as accident investigators. In the event of an accident, the NTSB will investigate, determine a cause, and make recommendations. After this, the FAA will carry out the recommendation through regulatory action. Take for example the deadly mid-air collision early this year at Reagan National Airport. The NTSB recently held a three day investigative hearing on the cause of the accident. In these hearings, investigators spoke with many aviation professionals, and used this as an opportunity to locate the root cause of the incident. Through this, the FAA will be able to take action that makes aviation safer in the future.

Faith, Stewardship, and Responsibility

“Every Workplace. Every Nation.” This is the motto of LeTourneau University, what some would say is the best aviation program in the country. At the heart of this excellence is the integration of a Christian worldview into every action. We have a responsibility to bear as witnesses for Jesus Christ in this world. We must allow our actions to glorify the Spirit at work within us. While, yes, this can mean ministry and mission work, it also means being aware of every action we take. In aviation, we must be good stewards of the people entrusted into our care by the grace of God. This naturally leads to a desire to be safe. In fact, safety is a deeply Christian idea. We are called to be humble. In the same sense safety is a humble pursuit. If everything goes as planned, most people will not ever know about what it took to get there. We must not expect recognition or congratulations for simply doing the work God has laid out for us. To this effect, safety is not merely for aviation. In many complex industries we must remember that lives are on the line and an ultimate responsibility has been entrusted to us.Every industry where lives are at stake should look to the aviation system as a model for excellence.

Sources

Alston, G. (2016). How Safe Is Safe Enough? Leadership, Safety and Risk Management. Routledge.

Federal Aviation Administration. (2025, May 13). Aviation Safety Action Program | Federal Aviation Administration. FAA. Retrieved September 26, 2025, from https://www.faa.gov/about/initiatives/asap

Hansen, M., McAndrews, C., & Berkeley, E. (2008, July). HISTORY OF AVIATION SAFETY OVERSIGHT IN THE UNITED STATES. faa.gov. https://www.faa.gov/about/office_org/headquarters_offices/avs/offices/aam/cami/library/online_libraries/aerospace_medicine/media/1105.pdf

Reason, J. (1997). Managing the Risks of Organizational Accidents. Ashgate.

Leave a comment